Of course this does not mean that education is without value. I have spent many, many hours educating myself – and I certainly don't consider that wasted time. But...for every hour I've spent educating myself, I've probably spent 20 hours practicing (all outside of any work context).

Personally, I think the quickest way to develop practical skills in software engineering (and, again, likely also in many other areas) is just such a lopsided mix of education and practice. I suspect the ideal ratio is different for different people, and also different over the course of a career. In my own case, I note that I can proportionally spend more time these days on educating myself, especially so when the subject matter is an extension of something I've already mastered.

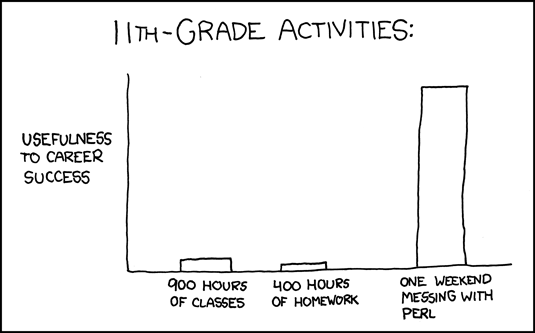

The real point here is that formal educations that spend far more time empahsizing reading and lecture than they do practice seem wildly out of whack to me. My strongest evidence is the readiness of recent graduates to actually do something useful in the workplace – it's close to zero.